Quantification of substrate-dependent defect signatures in monolayers of TMDCs using TEM and spectroscopy

August 7, 2024 – Researchers from Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg and Ulm University (Germany) have developed a method to correlate atomic defect densities in transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers with their optical spectroscopy signatures. Using the chromatic and spherical aberration-corrected SALVE microscope at 80 keV, the team creates controlled sulfur vacancies in MoS2 and WS2, then transfers the irradiated samples to various substrates for Raman and photoluminescence analysis. The study identifies polystyrene as optimal for detecting defect-bound excitons via photoluminescence, while SiC and Si/SiO2 substrates prove ideal for Raman-based defect quantification—laying the groundwork for fast, reliable optical quality control of 2D material-based optoelectronic devices.

Two-dimensional materials have captured growing attention from the scientific community due to their unique optical and optoelectronic properties.[1],[2] Among these materials, semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) such as MoS2 and WS2 stand out because they undergo a transition from an indirect to a direct band gap when thinned from multiple layers down to a single atomic layer.[3],[4] This band gap transition enables more efficient absorption and emission of photons in monolayers, resulting in a dramatic enhancement of photoluminescence (PL).[5] These characteristics make TMDC monolayers highly promising candidates for optoelectronic devices including LEDs, lasers, solar cells, and photodetectors.[6] However, the optical behavior of these materials depends critically on both their atomic defect structure[7] and their interaction with the underlying substrate.[8]

Aberration-corrected (scanning) transmission electron microscopy (S-TEM) provides a powerful approach for generating defects while simultaneously imaging the resulting atomic structure.[9],[10],[11] The technique enables precise control of defect generation rates in TMDCs, though electron energies of 80 kV and below are required for this purpose.[12] The chromatic and spherically aberration-corrected (CC/CS) SALVE instrument at Ulm University proves ideally suited for such investigations.[13] Studies have established that electron beam irradiation at 80 kV exclusively produces chalcogen vacancies in these materials.[12],[13],[14],[15]

Within the electronic band structure of TMDCs, chalcogen vacancies act as n-type dopants.[16] First-principles calculations can predict the presence of defect states appearing within the band gap.[17] When excitons—bound electron-hole pairs—become trapped at defects, their energy decreases. These defect-bound excitons produce a characteristic peak in the PL spectrum at energies below the free exciton emission.[18] More broadly, defect engineering offers a pathway to controlling both the type and concentration of charge carriers, which profoundly influences device performance.[2]

Correlating defect structures characterized in TEM with optical spectroscopy measurements presents two fundamental challenges. First, the techniques operate at incompatible length scales—TEM provides atomic resolution over small areas while optical methods probe much larger regions. Second, TEM requires the 2D material to be freely suspended on a grid, whereas practical device applications demand an understanding of how substrate-supported TMDCs behave optically. Previous research has explored how larger defects such as pores affect Raman spectra.[7]

To bridge this gap, the research team employed a previously developed back-transfer technique[19] that allows electron-irradiated MoS2 and WS2 to be moved from TEM grids onto various substrates for subsequent optical characterization. This innovative approach makes it possible to correlate the defect density created by TEM irradiation of a freely suspended TMDC flake with optical spectra acquired from the same irradiated region after transfer onto polystyrene (PS), Si/SiO2, or SiC substrates.

In the first experimental series, the scientists determined defect densities from atomically resolved HRTEM image sequences (Fig. 1). An automated defect detection algorithm, which identifies vacancies based on statistical intensity differences at lattice sites, was applied to each frame in the series. The measured defect density could then be related to the cumulative electron dose delivered to that point. At the electron doses employed, only isolated single or double sulfur vacancies were observed, indicating that the defect generation rate (damage cross-section) remains constant under these conditions. The data in Fig. 1 confirm this linear behavior. By extrapolating to lower doses, the team determined damage cross-sections of 6.1 barns for MoS2 and 8.6 barns for WS2, with intrinsic defect densities of zero for MoS2 and 0.11 nm−2 for WS2.

The second experimental series involved irradiating specific flake regions at low magnification using a large field of view, without atomic resolution imaging. This approach enabled lower electron doses and defect densities to be achieved over larger areas than in the first series. Using the damage cross-sections and intrinsic defect densities established from the first experiments (Figs. 1e and 1f), the researchers calculated the actual defect densities in regions probed by optical spectroscopy. In cases where the irradiated area was smaller than the laser spot, an effective defect density was computed by averaging—representing the density that would result if all defects were uniformly distributed across the illuminated region. This correction applied to the three highest irradiation doses on Si/SiO2 and the highest dose on PS. Fig. 2 presents optical microscopy images of all samples and substrates used in these optical studies.

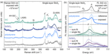

The Raman spectroscopy results (Fig. 3a) reveal how single-layer MoS2 responds to electron irradiation after back-transfer to Si/SiO2 substrates. Different sample areas received doses ranging from 3.1 × 104 to 2.9 × 107 e− nm−2, while unirradiated regions served as references. The reference spectrum displays the characteristic first-order Raman modes: the in-plane E′ mode at 386 cm−1 and the out-of-plane A′1 mode at 402 cm−1, along with the second-order 2LA(M) mode at 436 cm−1.[20] Additionally, a weak peak appears at 220 cm−1—a signature of crystal defects in MoS2 assigned to the longitudinal acoustic LA(M) phonon near the M-point of the Brillouin zone, which becomes Raman-active through defect-induced symmetry breaking.[21],[22] This defect-activated mode has previously been observed at 225 cm−1 in functionalized MoS2 powder and at 229 cm−1 in mechanically exfoliated functionalized samples.[23] Its appearance in nominally unirradiated reference measurements likely stems from minor defects introduced during the back-transfer process. Notably, the LA(M) mode intensifies substantially in electron-irradiated regions, demonstrating that not only larger defects created by gallium ions[7] but even individual sulfur vacancies at concentrations below 1% produce detectable Raman signatures.

The analysis further reveals that the LA(M) peak position shifts to higher wavenumbers with increasing defect density (Fig. 3b). The researchers used the intensity ratio between the LA(M) and 2LA(M) modes (ILA(M)/I2LA(M)) as a quantitative indicator of defect concentration, since the 2LA(M) mode—arising from a second-order process—requires no defects for activation. Fig. 3c shows that this ratio initially decreases slightly at low doses before rising as the defect density approaches 0.5%. The increasing ratio directly correlates with stronger absolute LA(M) peak intensity.

To examine substrate effects on the Raman response of irradiated MoS2, the team conducted additional measurements on freestanding MoS2 on TEM grids and on polystyrene, complementing the Si/SiO2 and SiC results (some PS data previously reported in Ref. 19). Fig. 4a compares spectra obtained at 633 nm excitation for samples receiving the same electron dose of 107 e− nm−2. Light-colored traces represent unirradiated references while dark traces show irradiated regions. Following irradiation, the defect-induced LA(M) Raman mode appears most prominently on Si/SiO2 and SiC substrates, less distinctly on polystyrene, and only weakly on freestanding samples.

Photoluminescence measurements (Fig. 4b) provided further confirmation of how substrates influence exciton energies and defect detection in MoS2. The PL spectra are directly comparable within each panel due to identical experimental conditions. For systematic comparison, the team selected an intermediate electron dose of 1.5 × 106 e− nm−2. Freestanding MoS2 in its unirradiated state exhibits A (1.83 eV) and B (1.99 eV) exciton peaks.[24] After irradiation, an additional AB peak emerges at 1.70 eV, attributed to excitons bound to defect sites. The A exciton shifts upward by approximately 50 meV to 1.87 eV, while the B exciton shifts by about 40 meV to 2.03 eV after irradiation. In contrast, samples on PS, SiC, and Si/SiO2 show minimal changes in A-exciton energy between irradiated and reference regions. Nevertheless, the substrate itself profoundly affects the PL characteristics: on Si/SiO2, the spectrum becomes dominated by the A− trion—a quasiparticle combining an exciton with an extra electron—while the A-exciton peak at 1.84 eV appears suppressed as a mere shoulder. This behavior reflects substrate-induced n-doping that provides excess negative charges.[24] The PL spectrum of irradiated regions, including both exciton and trion features, remains largely unchanged. Two additional peaks at 2.12 and 2.14 eV, observed on irradiated MoS2 on both SiC and Si/SiO2, correspond to graphitic G and D Raman modes, possibly originating from the carbon film at TEM grid hole edges or from carbon contamination.

Comparison across substrates reveals that SiC produces lower substrate-induced doping than Si/SiO2, as evidenced by a more pronounced A-exciton peak. Unlike samples transferred to Si/SiO2 and SiC, MoS2 on polystyrene shows a shifted A-exciton position with no A− trion contribution. Instead, the defect-bound exciton AB near 1.70 eV displays markedly higher intensity on PS than on other substrates. This peak has been attributed in the literature to excitons bound at point defects or impurities—sometimes termed the L-band.[25] While the peak origin cannot be definitively resolved since both electron-created sulfur vacancies and carbon-containing contaminants could contribute, the clear visibility of the defect-induced LA(M) Raman mode on PS samples supports the interpretation that electron beam-induced vacancies play a significant role.

Across nearly all electron-irradiated regions—with the exception of freestanding samples—the intensity of the A-exciton emission decreases. The researchers attribute this reduction to defects functioning as non-radiative recombination centers where excited electrons and holes recombine without emitting photons. Taken together, the Raman and PL results demonstrate that multiple substrate platforms can serve to detect and study defect-induced bound excitons (AB) and defect-activated LA(M) phonon modes in MoS2. These include freestanding configurations, polystyrene, SiC, and Si/SiO2. Polystyrene proves optimal for observing bound excitons in PL, while Si/SiO2 and particularly SiC provide the best platforms for Raman-based detection of the defect-induced LA(M) mode. These findings establish an important foundation for developing optical quality control methods for optoelectronic devices based on 2D materials.

Resource:

Moses Badlyan, N., Quincke, M., Kaiser, U., Maultzsch, J. (2024).

TEM-processed defect densities in single-layer TMDCs and their substrate-dependent signature in PL and Raman spectroscopy.

Nanotechnology 35, 435001.

https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/ad6875

-

Koperski, M. et al. (2017). Optical properties of atomically thin transition metal dichalcogenides: observations and puzzles. Nanophotonics, 6, 1289–1308. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2016-0165

-

Liang, Q. et al. (2021). Defect engineering of two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides: applications, challenges, and opportunities. ACS Nano, 15, 2165–2181. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c09666

-

Mak, K. F. et al. (2010). Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett., 105, 136805. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.136805

-

Wang, G. et al. (2018). Colloquium: excitons in atomically thin transition metal dichalcogenides. Rev. Mod. Phys., 90, 021001. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.90.021001

-

Chhowalla, M. et al. (2013). The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem., 5, 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1589

-

Mueller, T. and Malic, E. (2018). Exciton physics and device application of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. npj 2D Mater. Appl., 2, 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-018-0074-2

-

Fujisawa, K. et al. (2021). Quantification and healing of defects in atomically thin molybdenum disulfide: beyond the controlled creation of atomic defects. ACS Nano, 15, 9658–9669. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c10897

-

Buscema, M., Steele, G. A., van der Zant, H. S. J., and Castellanos-Gomez, A. (2014). The effect of the substrate on the Raman and photoluminescence emission of single-layer MoS2. Nano Res., 7, 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-014-0424-0

-

Schleberger, M. and Kotakoski, J. (2018). 2D material science: defect engineering by particle irradiation. Materials, 11, 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11101885

-

Zhao, X., Kotakoski, J., Meyer, J. C., Sutter, E., Sutter, P., Krasheninnikov, A. V., Kaiser, U., and Zhou, W. (2017). Engineering and modifying two-dimensional materials by electron beams. MRS Bull., 42, 667–676. https://doi.org/10.1557/mrs.2017.184

-

Lehnert, T., Lehtinen, O., Algara–Siller, G., and Kaiser, U. (2017). Electron radiation damage mechanisms in 2D MoSe2. Appl. Phys. Lett., 110, 033106. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4973809

-

Kretschmer, S., Lehnert, T., Kaiser, U., and Krasheninnikov, A. V. (2020). Formation of defects in two-dimensional MoS2 in the transmission electron microscope at electron energies below the knock-on threshold: the role of electronic excitations. Nano Lett., 20, 2865–2870. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c00670

-

Linck, M. et al. (2016). Chromatic aberration correction for atomic resolution TEM imaging from 20 to 80 kV. Phys. Rev. Lett., 117, 076101. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.076101

-

Quincke, M., Mundszinger, M., Biskupek, J., and Kaiser, U. (2024). Defect density and atomic defect recognition in the middle layer of a trilayer MoS2 stack. Nano Lett., 24, 10496–10503. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.4c02391

-

Köster, J. et al. (2024). Phase transformations in single-layer MoTe2 stimulated by electron irradiation and annealing. Nanotechnology, 35, 145301. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/ad15bb

-

McDonnell, S. et al. (2014). Defect-dominated doping and contact resistance in MoS2. ACS Nano, 8, 2880–2888. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn500044q

-

Zhou, W. et al. (2013). Intrinsic structural defects in monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett., 13, 2615–2622. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl4007479

-

Tongay, S. et al. (2013). Defects activated photoluminescence in two-dimensional semiconductors: interplay between bound, charged and free excitons. Sci. Rep., 3, 2657. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02657

-

Quincke, M. et al. (2022). Transmission-electron-microscopy-generated atomic defects in two-dimensional nanosheets and their integration in devices for electronic and optical sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater., 5, 11429–11436. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.2c02491

-

Scheuschner, N., Gillen, R., Staiger, M., and Maultzsch, J. (2015). Interlayer resonant Raman modes in few-layer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B, 91, 235409. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.91.235409

-

Tornatzky, H., Gillen, R., Uchiyama, H., and Maultzsch, J. (2019). Phonon dispersion in MoS2. Phys. Rev. B, 99, 144309. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.99.144309

-

Frey, G. L. et al. (1998). Optical properties of MS2 (M = Mo, W) inorganic fullerene-like and nanotube material optical absorption and resonance Raman measurements. J. Mater. Res., 13, 2412–2417. https://doi.org/10.1557/JMR.1998.0335

-

Moses Badlyan, N., Pettinger, N., Enderlein, N., Gillen, R., Chen, X., Zhang, W., Knirsch, K. C., Hirsch, A., and Maultzsch, J. (2022). Oxidation and phase transition in covalently functionalized MoS2. Phys. Rev. B, 106, 104103. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.106.104103

-

Scheuschner, N., Ochedowski, O., Kaulitz, A.-M., Gillen, R., Schleberger, M., and Maultzsch, J. (2014). Photoluminescence of freestanding single- and few-layer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B, 89, 125406. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.89.125406

-

Yagodkin, D. et al. (2022). Extrinsic localized excitons in patterned 2D semiconductors. Adv. Funct. Mater., 32, 2203060. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202203060